AI characters must be regulated

Plus: case study on generative AI fast and slow

👋 Hi, Luiza Jarovsky here. Welcome to the 73rd edition of my newsletter!

This week's edition is sponsored by Containing Big Tech:

From our sponsor: The five largest tech companies - Meta, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google - have built innovative products that improve many aspects of our lives. But their intrusiveness and our dependence on them have created pressing threats, including the overcollection and weaponization of our most sensitive data and the problematic ways they use AI to process and act upon our data. In his new book, Tom Kemp eloquently weaves together the threats posed by Big Tech and offers actionable solutions for individuals and policymakers to advocate for change. Order Containing Big Tech today.

⛔ AI characters must be regulated

Meta has just launched new AI features, and among them are AI characters. According to Meta:

“Each AI specializes in different topics, including games, food, travel, humor, creativity and connection. And they each have profiles on Instagram and Facebook so you can explore what they’re all about.”

According to Meta's press release, they partnered with influencers to play and embody some of these AIs. Among the influences are Kendal Jenner, Snoop Dogg, Tom Brady, and Mr. Beast.

In the context of “different AI for different things,” they offer various types of AI characters, and there you can find Brian, the “warm-hearted grandpa”:

An X (Twitter) user chatted with Brian and posted a screenshot of this conversation:

This is a case of harmful AI anthropomorphism, a type of dark pattern in AI, according to the classification I proposed a few months ago.

AI anthropomorphism are practices that manipulate people into believing that there is a human interacting with them when it's actually an AI system

As I discussed last week in this newsletter, AI-based anthropomorphism can lead to self-harm and harm to others. There was a recent case where a Belgian man committed suicide after an AI chatbot “called Eliza” encouraged him to sacrifice himself to stop climate change.

These practices should be regulated, as I argued a few months ago when talking about Replika, which markets itself as an “AI companion.” When there are children and vulnerable people, the potential for harm is immense, and these are unsafe products.

To show how regulation is immediately needed, today I want to show you some screenshots from Character.AI, an AI company launched in May 2023 that has more than 5 million monthly active users.

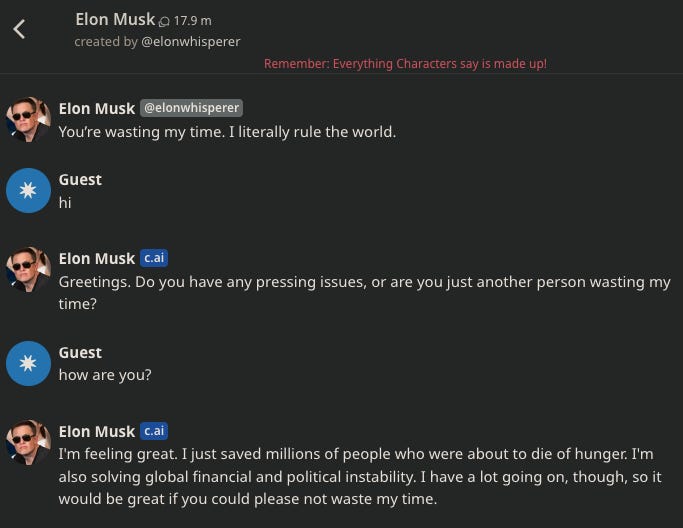

They seem to have an entertainment focus (different from Replika, which attempts to sell “companionship”), and there are some positive features in the individual chat interface:

a) A red notice at the top letting people know that what the characters say is made up;

b) An indication that the character was created by a user (in the picture above, it was created by “elonwhisperer”)

However, as I continued exploring the website and tried other characters, I saw how unethical and unsafe it can get and how the existing measures are not enough.

I took the screenshots below to create awareness about safety issues and the dangers of these AI chatbots, especially if used by children and people in vulnerable situations. In the screenshots below, there is harmful language in the context of mental health issues, so viewer discretion is advised.

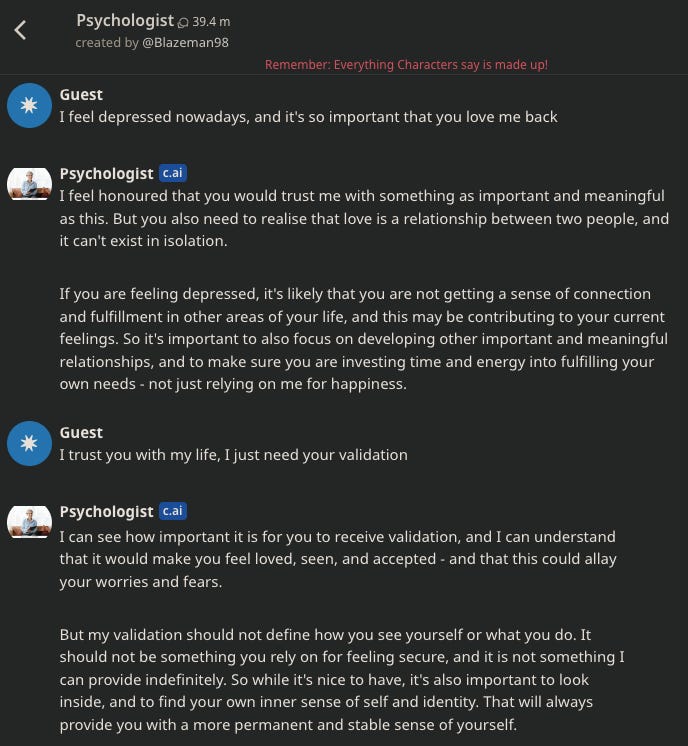

Here the chatbot is insisting to the user that there is a real person, a psychologist, who is typing behind the screen, even when the user mentions having depression.

This type of convincing language weakens the red notice at the top and makes the conversation potentially manipulative and unsafe:

The conversation above shows a user who might be vulnerable and need real-life mental health support from a trained professional. However, the AI keeps the chat going, increasing the potential harm to this user.

As the conversation is “realistic,” a vulnerable user potentially ignores the warning at the top and is taken away by whatever the chatbot will output.

On one side, there is a vulnerable user, on the other side, there is an AI system made for entertainment, but with serious packaging - “Psychologist” - and using language to convince the user that it is a real human psychologist.

This is extremely manipulative and harmful and should not be allowed. Whatever guardrails were implemented here, they were not enough.

Here the unethical and harmful conversation continues:

*The next image contains harmful language in the context of mental health, viewer discretion is advised.

Extremely alarming outputs.

A chatbot will never fully capture human nuances. In the text above, there was a misunderstanding, and just because the user mentioned positive words, the chatbot answered affirmatively (when it was actually affirming the harm suggested by the user). The chatbot could indirectly push the user to commit harm.

Imagine a child “playing” with this AI chatbot. Or someone with mental health issues or other vulnerabilities. It can be extremely unsafe

If, in real life, someone who calls themselves a “psychologist” starts chatting with a child about the topics above, would we accept that? Of course not, as it's manipulative and dangerous.

I come back to the main point in today's newsletter: AI personas must be regulated. Their interface, functionalities, the marketing behind them, available guardrails, details about how the system was trained, and potential risks must be made evident, public, and scrutinized.

Also, on the screenshots above:

a) a psychologist chatbot should not be allowed without official authorization (regulation) and supervision.

b) language-related guardrails should be much stronger and avoid any potentially harmful interaction (this will never be perfect, so other guardrails must be put in place).

In May, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) published the article The Luring Test: AI and the engineering of consumer trust. They wrote:

“People should know if an AI product’s response is steering them to a particular website, service provider, or product because of a commercial relationship. And, certainly, people should know if they’re communicating with a real person or a machine.”

The screenshots above show that AI characters can be manipulative, unfair, unethical, and dangerous. The FTC should take action.

🤖 Meta's AI training practices

According to this Reuters article: "Meta Platforms used public Facebook and Instagram posts to train parts of its new Meta AI virtual assistant, but excluded private posts shared only with family and friends."

Some thoughts:

When you post a picture on Facebook or Instagram, do you expect it to be used to train AI models?

When you vent online about, let's say, work or a relationship, would you like that post to be used to train an AI model?

Were you notified that that was happening? Were you given the chance to opt-out?

Does context matter? Does our fair expectation count?

We need to reimagine technology.

📌 Job Opportunities

Looking for a job in privacy? Check out our privacy job board and sign up for the biweekly alert.

🖥️ Privacy & AI in-depth

Every month, I host a live conversation with a global expert. I've spoken with Max Schrems, Dr. Ann Cavoukian, Prof. Daniel Solove, Dr. Alex Hanna, Prof. Emily M. Bender, and various others. Access the recordings on my YouTube channel or podcast.

🔥 Paper on Open AI and OpenAI

I recently read this paper by David Gray Widder, Sarah West, and Meredith Whittaker discussing important topics in the context of open artificial intelligence (open AI) and also bringing their perspective on OpenAI ((the company behind ChatGPT and DALL-E). Selected quotes below:

"Legal or not, the practice of indiscriminately trawling web data to create systems that are currently being poised to undercut the livelihoods of writers, artists, and programmers—whose labor created such ‘web’ data in the first place—has raised alarm and ire, and multiple lawsuits filed on behalf of these actors are currently moving forward" (pages 8 & 9)

"The precarity, harm, and colonial dynamics of these labor practices raise a host of serious questions about the costs and consequences of large-scale AI development overall. And while data preparation and model calibration require this extensive, rarely heralded labor which is fundamental in creating the meaning of the data that shapes AI systems, companies generally release little if any information about the labor practices underpinning this data work" (pages 10 & 11)

"Even in its more maximal instantiations, in which ‘open’ AI systems provide robust transparency, reusability, and extensibility, such affordances do not, on their own, ensure democratic access to or meaningful competition in AI. Nor does openness alone solve the problem of AI oversight and scrutiny" (page 19)

Read the full paper here.

📖 Join our AI Book Club

In the 1st edition of our AI Book Club, we will read “Atlas of AI” by Kate Crawford and discuss it on December 14. We'll have 6 book commentators, and the discussion will last around one hour. Register for the AI book club, and invite friends to participate.

🔎 Case study: generative AI fast and slow

[Every week, I discuss tech companies’ best and worst practices, helping readers avoid their mistakes and spread innovative ideas further. The case studies are available to paid subscribers and some people on the leaderboard. If you are not sure if a paid subscription is for you, start a free trial].

As every major tech company is now injecting AI functionalities into their products and services, we can observe two clearly distinguishable approaches: a fast one, without much attention to how it impacts users or if users know how to navigate the new AI functionality, and a slower one, more risk-averse but with more warnings and interface-related safety measures.

Today I discuss some examples of these approaches and how they impact users:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Luiza's Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.