The New AI Nationalism

As countries’ economic, political, and legal priorities regarding AI become clearer, a new type of AI nationalism is emerging. We must make sure to keep global AI governance alive | Edition #218

👋 Hi everyone, Luiza Jarovsky here. Welcome to our 218th edition, with my weekly essay on AI's emerging legal and ethical challenges, now reaching over 68,000 subscribers in 168 countries. It's great to have you on board! To upskill and advance your career:

AI Governance Training: Apply for a discount here

Learning Center: Receive free AI governance resources

Job Board: Find open roles in AI governance and privacy

AI Book Club: Discover your next read in AI and beyond

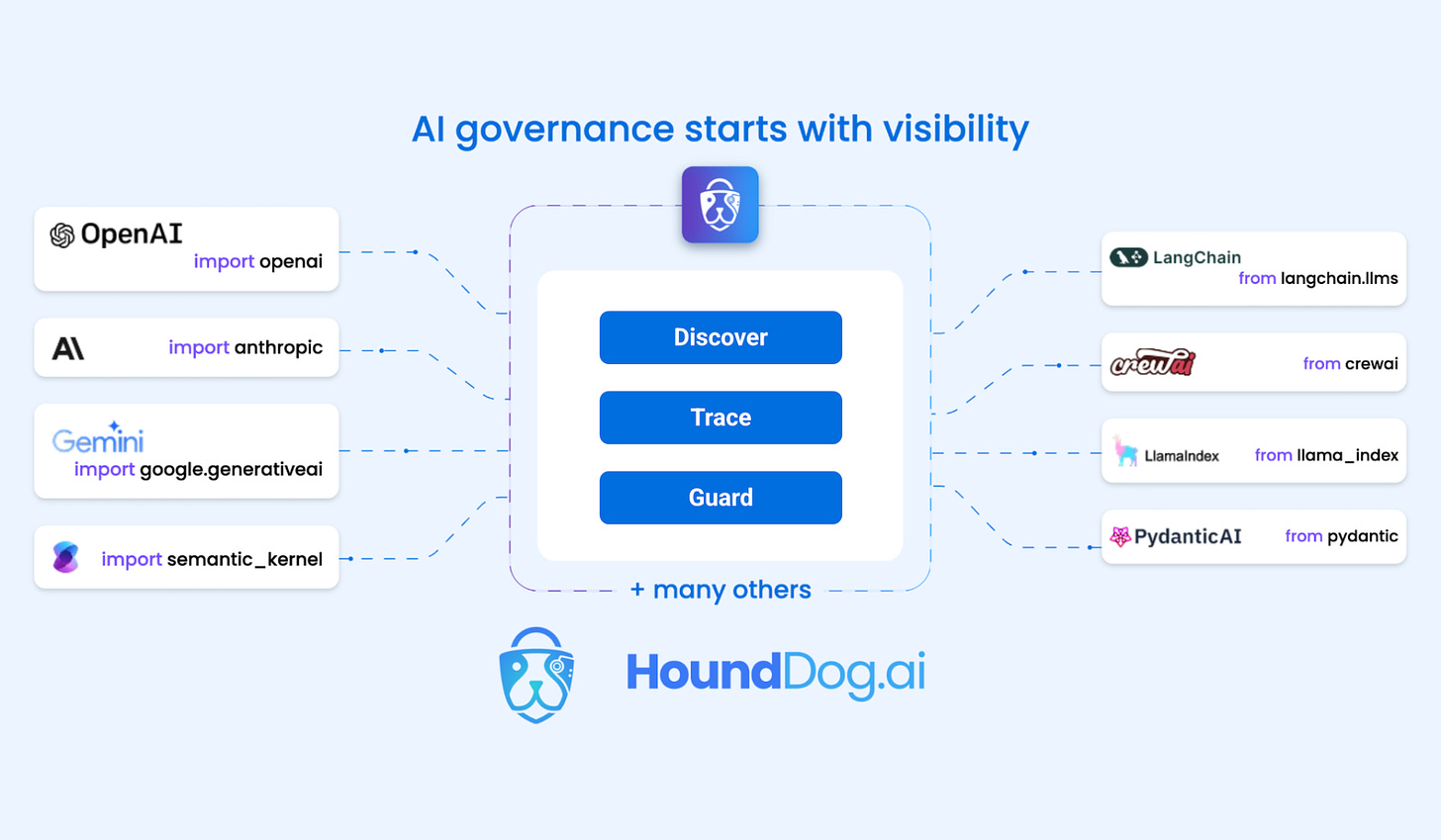

👉 A special thanks to HoundDog.ai, this edition's sponsor:

Is your org expanding its AI use cases? HoundDog.ai’s static code scanner enforces data minimization from the first line of code by applying guardrails to the types of sensitive data apps can expose to LLMs. Whitelist approved data types and block unauthorized PII before production. Shift privacy left by embedding it into every commit and pull request. Try HoundDog.ai's free static code scanner today.

The New AI Nationalism

At the beginning of the generative AI wave, despite the visible AI race, especially between the U.S. and China, there was still hope of finding common ground for effective global AI governance mechanisms.

As time passed, countries’ economic, political, and legal priorities regarding AI became more evident, and we are starting to see a new type of AI nationalism emerge.

In today's edition, I argue that these might be positive developments - if we manage to keep some level of global AI governance alive.

-

In recent years, it has become clear that many countries have been treating AI as a non-negotiable strategic national project that will shape economic and political influence in the upcoming decades.

China was among the first to realize it: in March 2016, AlphaGo (an AI system developed by Google DeepMind) defeated a South Korean champion at Go, a traditional and complex Chinese game.

The competition was watched by over 280 million people in China. In the following year, AlphaGo defeated China’s 19-year-old champion.

These were symbolic and decisive moments for China. A few months later, the Chinese government published a national AI strategy, announcing the country's goal of becoming the global centre of AI innovation by 2030.

In 2017, the U.S. National Security Strategy announced that the U.S. would prioritize emerging technologies critical to economic growth and security, including AI, to maintain its competitive advantage. It specifically mentioned Russia and China as challenges to American power, influence, and interests.

Despite old rivalries, in the following years, various global AI governance efforts were initiated, including the AI for Good Summit (2017), the Global Partnership on AI (2018), the OECD AI principles (2019), the UNESCO recommendations on AI ethics (2021), the G7 Hiroshima Process (2023), and the UN high-level advisory body on AI (2023).

Despite the hopeful sparks of a global consensus on AI governance, disagreements between traditionally non-rival countries started to appear, signaling that the old mold might not suit the new reality.

For example, in the Paris AI Action Summit earlier this year, the UK and the U.S. declined to sign the "Statement on Inclusive and Sustainable AI."

The U.S. cited overregulation, and the UK argued that there was a lack of clarity on global governance and national security challenges.

In 2025, new cracks and disagreements became more prominent, particularly those related to legal and ethical approaches to AI, leading to the emergence of a new type of AI nationalism: