Whether you like it or not, TikTok’s numbers are impressive. It has over 1 billion monthly active users. It was downloaded 3 billion times worldwide, and it is so far the most downloaded app this year. The average user opens TikTok 8 times per day. Globally, children spend an average of 75 minutes per day on TikTok, making it the social media platform they use most. With these astounding numbers, TikTok must have something special, right? Well, it has. It uses manipulative user experience (UX) design to keep users glued to it. It is built to trigger compulsive use, especially in more impressionable audiences such as teenagers. It is also harmful to privacy. I used TikTok for 30 days, and in this edition of the newsletter, I will explain why and how it is manipulative, addictive, and negatively affects users’ privacy.

Manipulation and Addiction

TikTok wants you hooked since you log in. The first page after you open the app is the “For You” page, where short videos carefully selected to grab your attention will be displayed. The videos are shown in full portrait mode, occupying almost all of the device’s interface. There is no signalization of progress or duration of the experience, completing the full immersion and the optimization for maximal consumption. As TikTok knows exactly what you are seeing and how many seconds you stop on each video, it will select videos for you that can intrigue you in a similar way, keeping you hypnotized.

The videos are in autoplay and shown in an endless scroll. These are features known for triggering addictive behavior, and there were legislative plans in the United States to ban them. It does not stop there: differently from Twitter or Facebook, the user cannot scroll up fast and jump a few videos. Whatever the strength of your scroll, you will be shown the next video TikTok selected for you, one by one — or keep moving your finger to actively scroll up after each video begins. They are in control of what you see, not you. This is stimulating and certainly will be another trigger for compulsive use, as the content placed on the “For You” page is statistically tailored to be the most captivating possible for you. Their data is optimized and personalized to steal as much attention as possible.

On TikTok, there is no space for long descriptions or external links with further information — which would possibly take the user out of the app. They want you to stay mesmerized there. TikTok videos usually contain subtitles so that even if you are at work or somewhere where you could not let the sound on, you can still engage with the content. If you watch a trend that you want to participate in, simply tap on the soundtrack name, and a pink “use this song” button will start pulsing at the bottom of the app. You are invited to participate! The various stimuli for users to become creators have worked, as it is estimated that 83% of TikTok users have also created content.

However, these 83% user-creators now have a challenge: successful content on TikTok must follow a certain formula. Videos must be short, fast, quickly awe-inspiring, and preferably using soundtracks, filters, effects, descriptions, tags, and content that are currently trending in the app. To thrive on TikTok, you must be fixated on it. You must use it frequently to know what is trending on the app. Otherwise, you will lose the timing — and timing is everything. Is there a popular dance everybody else is doing? Stop what you are doing, get dressed, get your phone in the vertical position and start recording now. The path to TikTok success is joining micro-trends and mimicking successful videos highlighting your personal touch in a bandwagon-compulsion style. If you are a teenager and you missed a trend, you lost a valuable opportunity for online popularity and social validation among your peers.

On this topic, teenagers have stated that their social lives currently revolve around TikTok: new trends, dances, viral videos, emerging stars, who is popular over there and who is not, and what is cool and what is not. The power of TikTok’s algorithm over today’s youth is inconceivable. Getting together is an opportunity to attempt a viral TikTok, so get your phones ready.

Regarding the content available on TikTok: it is known that creators have 3 seconds to enchant the viewer. Otherwise, their video will be thrown into TikTok’s forgetfulness blackhole. To captivate in 3 seconds, the content must essentially be outstanding: either shocking, irreverent, socially awkward, scary, performing admirable abilities, showing exposed bodies, and so on. There is no room for ordinariness. Using filters, effects, pop music, and elements that give the video an upbeat vibe and an accelerated pace is almost a must — unless you are already a TikTok celebrity, then you can do whatever you want, and your flock will rain likes and comments on you.

TikTok is not a suitable place for content that is purely informative or educational, that follows a normal learning pace, that lasts more than 1 minute, that has an introduction, a development, and a thoughtful conclusion, that does not use filters, music or ‘pyrotechnic’ effects, that does not try to be catchy or oversimplify things, that does not focus on dazzling in the first 3 seconds. There is no time for deeper reflections, critical thinking, or autonomy to process if what was seen makes sense or not. Everything is so fast that viewers just have the content pushed down their throats. Users are passive and paralyzed, waiting to be amazed. If a video has thousands of likes and interactions, it becomes viral, then it becomes socially validated as desirable and cool, then it becomes a micro-trend, then it is repeated thousands of times with little twists by people around the world, and then it becomes a cultural truth. This is the power of TikTok. That is how today’s youth are consuming information and how they receive important messages about what is personally or socially desirable. Whatever is "TikTok relevant" will have passed the test of capturing the viewers' attention in 3 seconds. I am not sure if any real-life, meaningful content can pass this test. But in any case, this is the type of content that teenagers have been consuming for an average of 75 minutes a day.

Besides deceptive patterns in terms of design and algorithm that I mentioned above — aimed at gluing TikTok users to the screen indefinitely — there are two additional factors that are triggers for compulsive behavior:

Dopamine shot from likes and subscribers

The first element is common to other social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, where the user is conditioned to value likes, shares, comments, and subscribes almost as a true validation of their personhood. Every time someone receives a like or a subscribe on TikTok, the person gets a dopamine shot in the brain, and it feels good. To get more dopamine hits, the person needs to keep posting popular content. On TikTok, as we saw above, it means that the person needs to keep looking for trends, soundtracks, hashtags, and challenges to replicate. The user is captured through his or her brain chemistry and now cannot stop engaging with the app.

Everything is impressive and intermittent reinforcement

The second element is that everything on TikTok is astonishing and made to charm in 3 seconds. However, not all videos are exactly delightful to you; some are, and some are not. This makes the user enter an intermittent reinforcement loop, as Dr. Julie Albright, a sociologist specializing in digital culture, explained to Forbes:

“when you’re scrolling … sometimes you see a photo or something that’s delightful and it catches your attention … and you get that little dopamine hit in the brain … in the pleasure center of the brain. So you want to keep scrolling.”

Sometimes you see something delightful to the brain, and sometimes the content does not provoke the same reaction. You cannot stop strolling until you find another delightful content to get more dopamine. This intercalation, in psychological terms, is called intermittent reinforcement, and there is extensive research on the topic.

“In behaviorism, Intermittent Reinforcement is a conditioning schedule in which a reward or punishment (reinforcement) is not administered every time the desired response is performed. This differs from continuous reinforcement which is when the organism receives the reinforcement every time the desired response is performed.”

When younger audiences, who are still maturing and forming their character and worldview, see something that intrigues them, they will be fixated on the app to find other similarly exciting things. Children and teenagers are much more impressionable. That explains how kids can spend 75 minutes a day scrolling on TikTok.

Privacy

In addition to the triggers for compulsive behavior, there are also relevant privacy concerns on TikTok. There are three different types, as I will explain now.

The first type refers to TikTok’s privacy policies and practices within the app. In 2020, they were caught spying on keystrokes. According to The Economic Times:

“TikTok starts collecting data the minute you download the app. It tracks the websites you’re browsing and how you type, down to keystroke rhythms and patterns, according to the company’s privacy policies and terms of service. The app warns users it has full access to photos, videos and contact information of friends stored in the device’s address book, unless you revoke those permissions”

More recently, they were accused of aggressive data harvesting, where they requested many more permissions than necessary to make the app work. According to Robert Potter, co-CEO of Internet 2.0, “when the app is in use, it has significantly more permissions than it really needs. (…) it grants those permissions by default. When a user doesn’t give it permission … [TikTok] persistently asks. (…) If you tell Facebook you don’t want to share something, it won’t ask you again. TikTok is much more aggressive.”

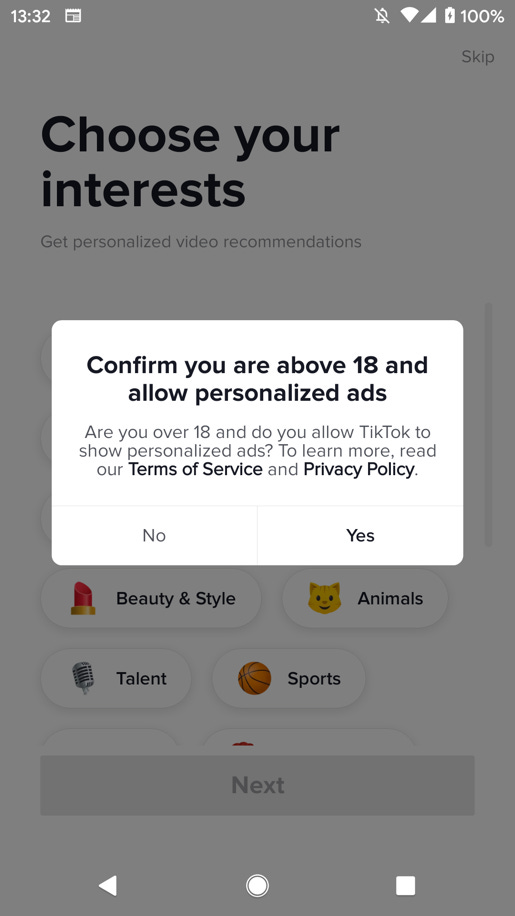

Additionally, TikTok uses deceptive design to make users share more data than they would do if they had more information. Take a look at the screenshot below, taken from TikTok’s sign-up process. The pop-up asks, “are you above 18, and do you allow TikTok to show personalized ads?” Is the question regarding age or advertising? As the two questions are merged, the user is forced to simply say yes to advertising. This is a typical case of deceptive design in data protection, as they confuse the user to make it difficult for him or her to have a privacy-preserving attitude.

The second type of privacy concern is regarding surveillance, spying, and censorship from China, given that TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, is China-based. In June 2020, India banned TikTok for surveillance and cybersecurity concerns. President Trump also threatened to do the same in the United States, although the plan was not continued by President Biden.

More recently, a member of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States called for a ban on TikTok from Google and Apple app stores due to fears of cybersecurity issues related to data transfers to China. It all began with a BuzzFeed News report, which showed that employees of TikTok’s parent company, located in Beijing, had accessed personal information from users located in the United States. According to a letter sent on June 30th, 2022 to the New York Times by TikTok’s CEO Shou Zi Chew, some employees in China in charge of clearing internal security protocols can indeed access certain information from United States-based TikTok, such as public videos and comments.

TikTok’s CEO guaranteed that the information was not being shared with the Chinese government and that it was subject to “robust cybersecurity controls.” However, given the Chinese government’s extensive surveillance and censorship practices, it is impossible to know for sure what is really happening with the data.

Some commentators have also pointed out the remarkable difference in terms of TikTok’s content in China (where TikTok is called Douyin) and in the rest of the world. Allegedly, the app promotes “engineering and maths in China while making youth in other countries addicted to twerking and porn.” Additionally, the Chinese version of TikTok “implements stricter rules and prohibits ‘deviant’ and ‘anti-government’ discussions.” For people under 14 years old, China limits the usage of the TikTok equivalent to 40 minutes a day and bans the app for these audiences between 10 pm and 6 am, intending to inhibit internet addiction. No similar measures against teen addiction were implemented in other countries, despite it being a known negative outcome of social media use. Given these developments, the Buzzfeed News article remarked that:

“There is, however, another concern: that the soft power of the Chinese government could impact how ByteDance executives direct their American counterparts to adjust the levers of TikTok’s powerful “For You” algorithm, which recommends videos to its more than 1 billion users. Sen. Ted Cruz, for instance, has called TikTok “a Trojan horse the Chinese Communist Party can use to influence what Americans see, hear, and ultimately think.”

TikTok is newer and much less scrutinized than Facebook and Google. We must follow up on how the discussion will be conducted within the FCC and possibly in the European Union when the Digital Services Act (DSA) enters into force. For now, it is unclear what happens with TikTok user data in China and if there is any type of influence from the Chinese government on how the algorithm works.

The third type of privacy concern is regarding children's and teenagers’ privacy. The first problem is sharenting. It can be defined as the practice by a parent or caregiver of online documenting moments in the life of a child or teenager. Parents that are using TikTok soon realize that showing their kids in videos can generate good results in terms of likes and subscribers, therefore, for their next dopamine hit, they exchange their kids’ privacy for likes. There are serious privacy and security issues involved in sharing anything about a child or teenager online, including identity fraud, exposing the child to predators, and cyberbullying.

There is also the matter of lack of consent, as children are sometimes too small to understand what is going on, and even when they can understand and consent, they are not consulted by the parent. Therefore it is possible that a few years from now, the child will be unhappy to discover that valuable private moments were shared on TikTok by the parent, perhaps in a sensationalized or embarrassing way, to fit a trivial trend. Remember that we, the parents, are from a different generation, and what we find acceptable and cute might see as inexcusable and creepy. Lastly, whatever is uploaded online has the potential to be circulating forever, as it takes only one screenshot or re-upload for that, aggravating the privacy risk.

Another issue is children and teenagers’ unintentional self-exposure to malicious individuals and predators online. Given TikTok’s extreme popularity with younger audiences, there should be stricter safeguards in place to avoid this type of vulnerability and potential harm. Younger audiences should also be alerted that whatever they upload will be digitally available forever, and ill-intentioned third parties could misuse it. Children and teenagers are frequent victims of cyberbullying and abusive behavior, so additional safeguards should be made available to protect their privacy.

I created an account on TikTok with the sincere hope that there was space for informative content. I wanted to share my expertise — privacy and data protection — in a way that was both entertaining and informative, where I would entice discussion and provoke reflection, especially among young viewers. When reading about TikTok’s best practices, I understood that if I wanted to reach meaningful audiences, I should be joining music/dance/challenge trends and adding popular soundtracks, hashtags, filters, and effects to my videos. Most importantly, I should spend time in the app watching and mimicking the successful content of other creators in fields similar to mine so that I could teach TikTok’s algorithm to whom to push my content. My videos should be fast-paced, short, and impressive. They should ideally be between 15 seconds and 1 minute long, and I should hook my viewer in the first 3 seconds. These best practices did not make any sense to me or for what I hoped to achieve with my content. They were not like Twitter, LinkedIn, or YouTube’s best practices, which leave plenty of space for thoughtful and critical content to flourish in its own way. To have my content viewed on TikTok, I would have to be one more engine in the addiction machine. This is not how I see myself or how I think about creating and consuming content.

I am a realistic person. I am sure that there are adults having fun, people making good money as influencers, and brands doing their usual marketing on TikTok. People can choose for themselves what they want for their lives — and I hope this article can offer useful information about the design tricks, algorithm twists, and brain chemistry behind TikTok’s fascination. Informed consent is power.

I am mostly concerned with children and teenagers. Their values, character, and worldview are still in formation, and they are frenetically pushed to consume, create and overvalue content that is very short, fast, trendy, mimicked, edited, filtered, and made to impress in 3 seconds. It is content for TikTok’s growth and profit and not content for education. Teens also feel strongly trapped in the dopamine cycle that makes them crave likes and subscribers — being pushed to trivialize their bodies and privacy if necessary — for just another dopamine hit and more social validation among equally glued peers.

TikTok is the epitome of the unregulated attention economy. It optimizes algorithms and design to capture not only users’ attention but also their time, personal data, brains, and feelings. The lack of scrutiny is so big that they can do it freely, profiting from the most impressionable and sensitive audience: teenagers.

My hope, as a mother of 3 small kids, is that until my kids start getting interested in social networks, there will be a robin-hood whistleblower that — in a tell-it-all style — will convince lawmakers, privacy advocates, and the public opinion that it makes no sense. It is unfair to use the ultimate power of design and algorithms to manipulate people and invade their privacy, especially the younger generation.

-

💡Thoughts? Questions?

What do you think are additional problematic issues with TikTok? What could be a regulatory solution for TikTok? Privacy needs critical thinkers like you: share this article and start a conversation about the topic.

See you next week. All the best, Luiza Jarovsky