Dark Patterns (Deceptive Design) in Data Protection

Learn how to identify and stop them from dictating your online choices

Dark patterns (or deceptive design), according to Harry Brignull - the first designer who coined the term - are “tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to, like buying or signing up for something.” Some common examples are websites or apps that make it almost impossible to cancel or delete an account, almost invisible links to unsubscribe from a non-requested newsletter, and insurance products that are surreptitiously added to your shopping cart. You can check more examples here or tweet and expose your own personal findings using the hashtag #darkpattern (they might be retweeted by this account - it's worth checking out some outrageous examples there).

One of the chapters of my ongoing Ph.D. in data protection, fairness, and UX design is about dark patterns in the context of data protection (you can download the full article I wrote on the topic here). I defined them as “user interface design choices that manipulate the data subject’s decision-making process in a way detrimental to his or her privacy and beneficial to the service provider.” In simple terms, they are deceptive design practices used by websites and apps to collect more personal data or more sensitive data from you. They are everywhere, and most probably, you encounter some form of dark pattern on a daily basis during online activities. Below are some examples of practices I call dark patterns:

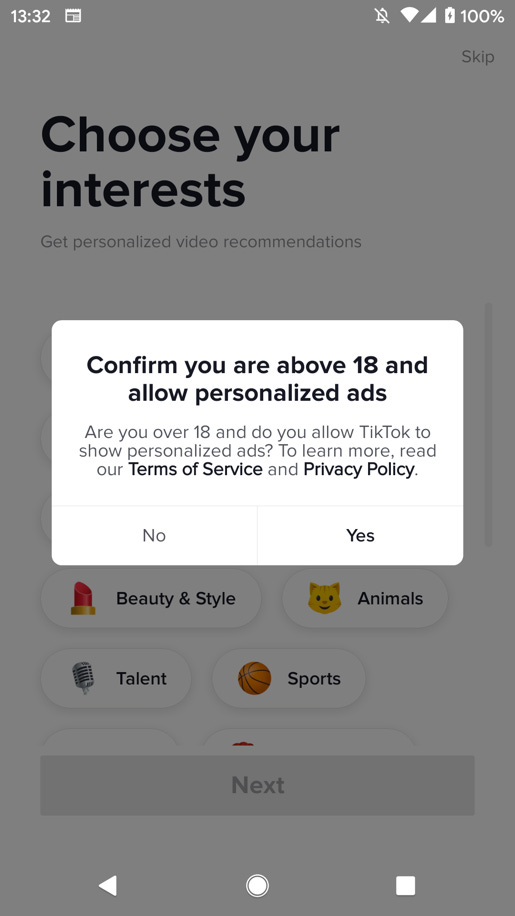

1- Screenshot from the TikTok sign-up page:

In this example, you cannot know if the “Yes” or “No” buttons are for the “are you over 18” or for the “do you allow TikTok to show personalized ads” question. According to my taxonomy, it would be a “mislead” type of dark pattern, as it misleads the data subject into not opting out of personalized ads.

2- Screenshot from Linkedin Settings:

Each of the sections above contains data protection-related choices (despite the fact that a few of the sections’ titles does not seem related to data protection), accounting for almost hundreds of options. This excessive amount of choices is not empowering; on the contrary, it distracts data subjects from important data protection choices and confuses them. This type of dark pattern is “hinder,” as by adding an excessive amount of choices, it hinders the capability of the data subject to choose according to his or her true preferences.

3- Screenshot from the website groopdealz.com:

Here, through manipulative language, the website is pressuring the data subject to add his or her email and subscribe to the newsletter, so the category of dark pattern is “pressure.” To read more about the taxonomy and the different types of categories and sub-categories, click here.

In the full article about the topic, I have discussed dark patterns’ mechanism of action and the behavioral biases that are exploited by them (showing how they manage to manipulate us to do something that was not our initial intention). I have also presented their legal status regarding the European General Data Protection Regulation - GDPR (no, they are not explicitly illegal) and offered a taxonomy to help us understand what is and what is not a dark pattern. Lastly, I proposed paths of regulatory changes that could help us move forward from here and improve the protection that is offered to us, data subjects.

My goal in talking about them in this newsletter is to increase awareness about the topic and to show that the design of websites and apps is not inoffensive or neutral. Design is a powerful tool to manipulate behavior, and sometimes - particularly because of behavioral biases - it is difficult to detect and avoid manipulative tricks, especially online.

What you can do as an individual is to try and be critical about your behavior online and why you are interacting with certain platforms in a certain way (what is your goal? What will you gain with that? What will the platform gain with that? Is is possible that you are being tricked into behaving in a certain way that is actually harmful to you?).

Online platforms that offer services that we love - such as Facebook, Twitter, Tiktok, Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, Tinder, and so on - are not “neutral.” They are companies working for (a lot of) profit, and an important input for them to make money is your personal data. Their foremost goal isn't doing good to people and to the world but pleasing shareholders (hopefully following the law). Law is not always (perhaps never) at the same pace as the technologies it is applied to (and related manipulative techniques to make them more profitable), so it is important that you are aware of what is happening and decide what is better for you.

See you next week. All the best, Luiza Jarovsky